The smell of fresh peanuts in the air. Frank Sinatra’s ‘Take me out to the ball game’ playing on loop. And the road to the World Series stretched out ahead. For fans of Major League Baseball, it’s officially a favorite time of year, but maybe not in 2020.

Despite spring training games being canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, regular season games began in late July. However, it’s not simply cardboard cutout fans who look different this year. Teams’ hometown financial situations aren’t playing out as in years past, either.

A Muni Bond’s Rookie Year: The Origins of Stadium Financing

Since the early 1950s, MLB Commissioner Ford Frick argued that professional sports generate significant revenue by hosting visiting teams and fans from other cities – revenue from which team owners did not benefit. Frick believed cities should support professional teams in return for their boost to the local economy and reputation, and his proposal to use subsidies and municipal financing to build and maintain sports venues sparked a decades-long economic debate.

The argument for using municipal financing to support stadiums and arenas is justifiable. Professional sports teams rally community pride. Games generate increased consumer spending. First-class venues can elevate a city’s profile and spur additional development nearby. Not to mention, the construction of such large facilities can create thousands of new (albeit temporary) jobs.1

However, opponents’ stance also makes sense. Municipal financing might be better reserved for infrastructure or education projects that have the potential to increase productivity and promote economic growth over the long term.2

Bond Structure and Subsidy Rankings

Stadium financing usually combines several types of municipal bonds: serial, term and capital appreciation bonds. Serial bonds mature gradually and in smaller units over the years. Term bonds come due all at once usually on longer maturities. Municipalities can make annual deposits to a reserve fund to call the bonds or make mandatory or optional calls. Capital appreciation bonds pay back investors in a single payment with principal reinvested at a stated rate that compounds along the way.

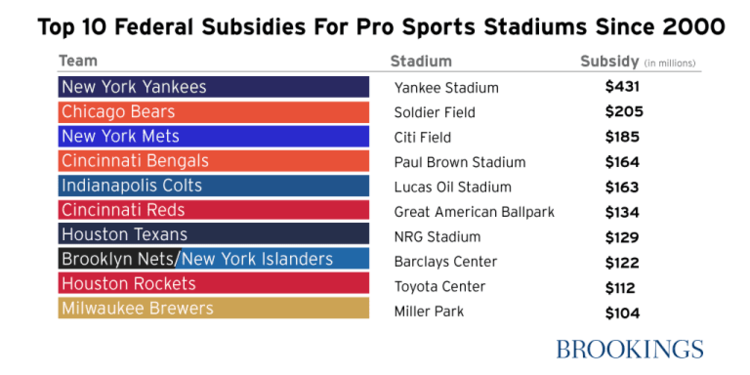

Regardless of how stadium financing is structured, the practice has been popular to support pro sports teams – illustrated by the following chart, which shows federal subsidies (in millions) for pro sports stadiums since 2000.

Bottom of the Ninth: Extra Innings or a COVID Shut Out?

Despite the ongoing debate ‘for or against’ municipal financing, I’d argue that the more important questions are related to the security of existing bond debt and the future of our modern-day Colosseums. Without paying fans in the stands this season, cities and counties are struggling with billions of dollars in debt. Budgets that were already under pressure with services such as water, sewer, roads and more now must make sports complex payments while they grapple with canceled games, no ticket sales and declines in taxes on tourism spending.

Since 2000, 40% of $17 billion in sports-related bonds were backed by taxes on tourism and other connected revenues. Support for these debt markets is drying up rapidly, but the severity of each city’s financial situation varies by individual exposure. Due to the pre-lockdown Super Bowl event, Miami Dade has collected twice the amount needed to cover interest payments on Marlins Park. However, Glendale’s stadiums and arenas represent two-thirds of the city’s public debt – a significant liability to cover without the economic boost of professional sporting events.

According to municipal analysts at Well Fargo Advisors, “The diverse revenue streams and reserve funds securing rated professional sports facility bonds should adequately protect bondholders during a short-term work-stoppage. However, … a prolonged downturn in consumer spending … makes this sector particularly susceptible to negative ratings actions and even payment defaults for the weakest credits.”3

So, when faced with an economic shutdown and global pandemic such as COVID-19, what’s the verdict on stadium bonds? Like many other things in 2020, they contain uncertainty but present a unique opportunity to reconsider the big picture. It’s time for cities to put all their cards on the table, dig into how they generate, maintain and reinvest revenue, and possibly start talking about a trade.

Wayne Anderman CFP® MBA is the founder of Anderman Wealth Partners, based in the Greater Fort Lauderdale Area, and a registered representative of Avantax Investment ServicesSM. Member FINRA, SIPC. Investment advisory services offered through Avantax Advisory ServicesSM.

These opinions are based on Wayne Anderman’s observations and research and are not intended to predict or depict performance of any investment. These views are as of the close of business on 08/31/2020 and are subject to change based on subsequent developments. Information is based on sources believed to be reliable; however, their accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. These views should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell any securities. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

1 Inglewood mayor- Near $3B Rams stadium to add 22K new construction jobs

2 The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums

3 Wells Fargo Advisors Municipal Insights COVID-19 – Municipal Bond Impact Quick Takes. 4/27/2020